Since 1990 I have been building sound-sculptures, instruments that produce wonderful, bizarre sounds and are intended also as arresting works of visual art. I have performed with these unique instruments in Tokyo, Hong Kong, at the Darmstadt sessions in Germany, at the Essl Museum in Vienna, and throughout the United States, including performances at SIGGRAPH in Los Angeles, Stanford University's CCRMA, at the Woodstockhausen Festival in Santa Cruz, and at the Kennedy Center. They have been employed in collaborations with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company and the Paul Dresher Ensemble, performed on by Speculum Musicae at Merkin Hall in New York City, and used in film soundtracks. Samples of the instruments have even found their way into the music of other composers. In 1996 Innova Records released a CD of my sound-sculpture improvisations. What follows are the liner notes from that CD. You can also click HERE to download a related essay called "Culture Sculpture".

Since 1990 I have been building sound-sculptures, instruments that produce wonderful, bizarre sounds and are intended also as arresting works of visual art. I have performed with these unique instruments in Tokyo, Hong Kong, at the Darmstadt sessions in Germany, at the Essl Museum in Vienna, and throughout the United States, including performances at SIGGRAPH in Los Angeles, Stanford University's CCRMA, at the Woodstockhausen Festival in Santa Cruz, and at the Kennedy Center. They have been employed in collaborations with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company and the Paul Dresher Ensemble, performed on by Speculum Musicae at Merkin Hall in New York City, and used in film soundtracks. Samples of the instruments have even found their way into the music of other composers. In 1996 Innova Records released a CD of my sound-sculpture improvisations. What follows are the liner notes from that CD. You can also click HERE to download a related essay called "Culture Sculpture".It was in 1990 that I designed and constructed my first sound-sculpture, an instrument called the mousetrap, out of junk, hardware, and found objects mounted on an electro-acoustic soundboard. The mousetrap was inspired by several antecedents, including the famous instruments of American composer Harry Partch. Most important—and proximate—was an instrument called the bug designed by Tom Nunn, a Bay Area musician and former University of California, San Diego student who continues to design fabulous instruments. I found the bug in contrabassist Bert Turetzky’s office (among other wonderful oddities, Turetzky included) and was immediately captivated, both aurally and visually. (The bug gets its name from its "antennae": two curled threaded rods.) The mousetrap, which includes a working mousetrap, was a response to the bug, a challenge "to build a better mousetrap." Instead I found that I had succeeded in building a bigger mousetrap.

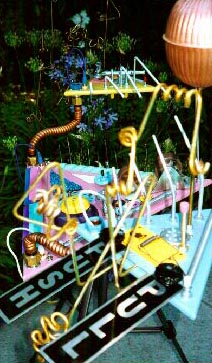

On this CD I play four instruments: the three-legged, table-sized mousetrap, the mini-mouse, a smaller instrument designed to sit on the music desk of a piano so that I can play both new and old instruments together, the duplex-mausphon, a two-tiered affair, and the midi-mouse (placebo 5-pin din jack comes standard) designed for Steve McKinstry and his Salmagundi Recording Studio.

The instruments consist of threaded rods, nails, wire strings stretched through a series of pulleys and turnbuckles, plastic combs, bronze braising rod blow-torched and twisted, doorstops, shoehorns, ratchets, steel wheels, springs, lead and PVC pipe, corrugated copper plumbing tube, Astroturf, parts from a Volvo gearbox, a metal Schwinn bicycle logo, and, indeed, mousetraps. It was great fun to collect this stuff and particularly satisfying to cause anxiety and suspicion among the hardware clerks who nervously eyed me as I conducted investigations of the acoustical properties of their wares. It was a feeling of accomplishment when, weeks into my research, the same salesmen would excitedly welcome me into the store, giddy with their own myopia-shedding epiphanies: "Mark, listen to how this thing sounds when you hit it with this!" My project became an informal and unexpected arts outreach program.

The pickups are 50¢ surplus piezo contact elements; there are eight pickups on the mousetrap, four per stereo side; the duplex mausphon is also a stereo instrument with one pickup on each of its two levels; mini and midi each have one pickup.

I play the sound-sculptures with my hands and with a number of different strikers and gadgets including Japanese chopsticks, knitting needles, combs, thimbles, plectrums, surgical tubing, a violin bow, and various wind-up toys, tops, etc. Located in the midst of the sculptures is a mixer and a small rack of electronic signal processors with their associated triggering pedals, mostly junky analog delays, early-era pitch transposers, unnatural reverbs, and the like. Signal-to-noise ratio has never been my greatest concern.

The sound-sculptures were intended as tools for improvisation and I have used them primarily in this capacity: in solo performances, such as the 90-minute improvisation in accompaniment to a 1993 Merce Cunningham Dance Company performance (an excerpt of which appears on this CD) and in ensemble contexts such as the S-tog Trio (a group which for one year played only my improvisation piece S-tog, a scheme based on the Copenhagen metro system and timetables). However, twice I have composed "formal" works using these instruments: Zero-One is a solo mousetrap composition that was performed by Steven Schick at the Darmstadt new music festival in 1992 and Scipio Wakes Up for the Paul Dresher Ensemble employs six micro-mice (very small sculptures comprised of only one playing surface); the Dresher piece was a fascinating and challenging project for me because the low-tech medium (the acoustic micro-mice) was "modulated" with a high-tech medium (the triggering of digitally transformed samples of the micro-mice).

There are many compelling aspects about these instruments (but, admittedly, drawbacks as well): their diverse sonic landscapes (which obscure a focused sonic personality), their hybrid material constitution (which requires diverse performance techniques), their miniature and portable nature (which limit their acoustical presence and necessitate electronic components), their unconventional and low-tech sensibilities which suggest broad creative responses (which in turn interact more remotely and tenuously with the mythic "communal musical discourse"), their uniqueness (which severely diminishes the development of a multi-user performance canon or common practice), their postmodern appropriation of disparate vernacular elements signifying a diffusion of transgressed cultural locations (their postmodern appropriation of disparate vernacular elements signifying a diffusion of transgressed cultural locations), etc.

Like all things in life one weighs advantages and disadvantages. At this point in my creative development, the exploration of these instruments makes me think about music deeply. That’s a big advantage.

Mark Applebaum (October, 1996)